Introduction: The Vital Role of Plants and Plant-Fungi Symbiosis

Plants form the foundation of terrestrial ecosystems, providing food, oxygen, and resources essential for human survival and the balance of natural environments. However, their growth and productivity often face challenges due to limited nutrient availability, especially of phosphorus (P), nitrogen (N), and other essential minerals. Efficient nutrient uptake is critical not only for maximizing crop yields but also for ensuring long-term soil fertility and sustainability.

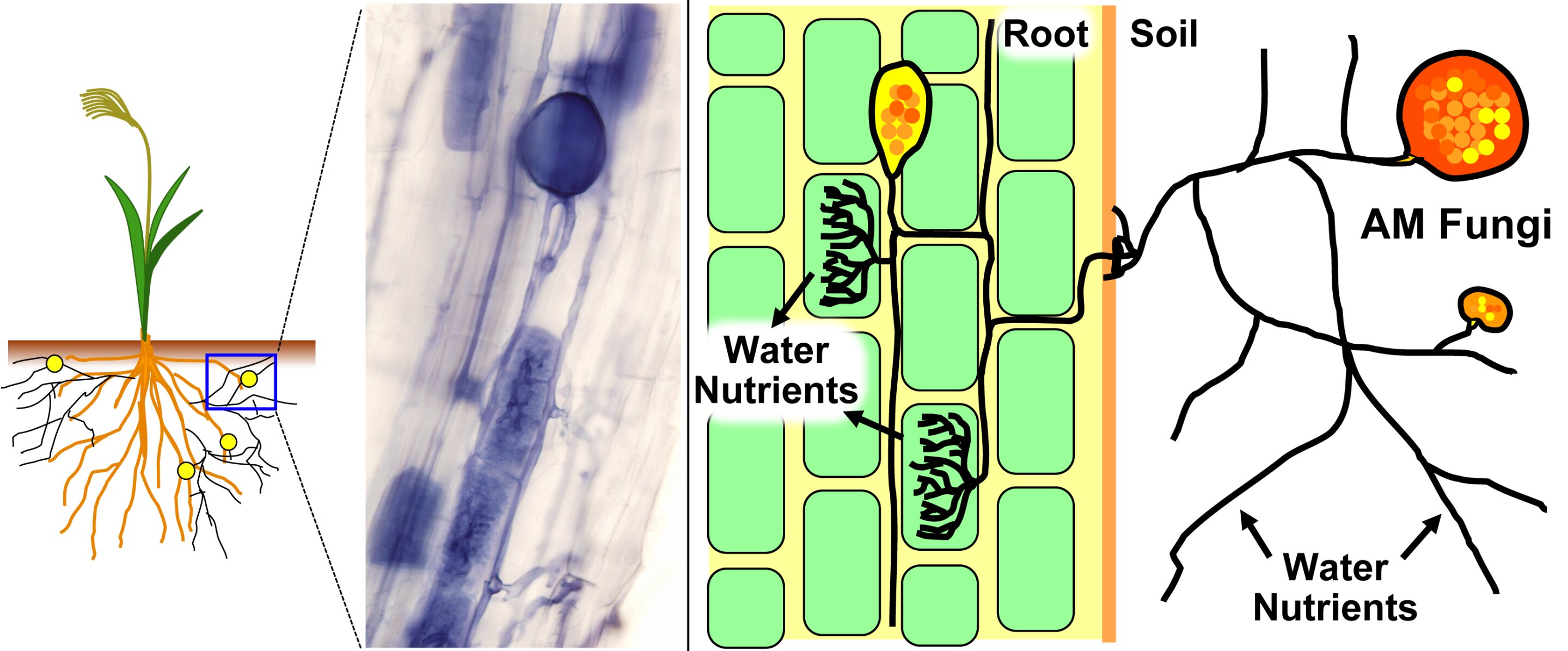

To overcome these challenges, many plants engage in a mutualistic partnership with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF). These fungi colonize plant roots and extend their hyphae deep into the soil, increasing the effective surface area for nutrient and water absorption. In return, the plant provides the fungi with carbohydrates derived from photosynthesis. This ancient and widespread symbiosis is especially important in nutrient-poor soils, where AMF can significantly enhance plant growth, resilience against stress, and overall productivity.

Beyond nutrient exchange, AMF also contribute to improved soil structure, greater resistance to drought, and reduced vulnerability to soil-borne diseases. Their role extends beyond individual plants, as they form vast underground networks that connect multiple plant species, facilitating nutrient sharing and supporting ecosystem stability. This blog post explores the remarkable influence of AMF on plant health and soil ecosystems, shedding light on their biological mechanisms, ecological significance, and potential in advancing climate-resilient and sustainable agriculture.

Key Facts on Plant Nutrition & Sustainability:

- Phosphorus plays a pivotal role in energy transfer, metabolic processes, and root development in nearly all plants.

- Excessive reliance on chemical fertilizers has adverse effects on soil health and long-term agricultural sustainability.

- AMF colonizes over 80% of terrestrial plants, significantly improving nutrient cycling and plant resilience, offering a natural biofertilizer alternative.

Understanding Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi: The Invisible Network

AMF are a specialized group of fungi belonging to the phylum Glomeromycota. Unlike many other soil fungi, AMF are obligate symbionts, meaning they cannot complete their life cycle without associating with a host plant. This partnership, known as arbuscular mycorrhiza, is one of the most widespread symbioses on Earth, occurring in approximately 80% of all land plant species, including a vast array of agricultural crops, trees, and grasses (Smith & Read, 2008).

In this mutualistic relationship, the plant, through photosynthesis, provides the fungus with carbohydrates (sugars) essential for its growth and metabolism. In return, the AMF's extensive network of fine, thread-like structures called hyphae extends far beyond the plant's root system into the soil. These hyphae are significantly smaller than root hairs and can access tiny soil pores and nutrient pools unavailable to the plant alone. This dramatically increases the plant's absorptive surface area, leading to enhanced uptake of crucial, often immobile, nutrients like phosphorus (P), nitrogen (N), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu) (Marschner & Rengel, 2012).

Within the plant root cells, AMF form characteristic structures:

- Arbuscules: These highly branched, tree-like structures are formed inside the plant root cells and are the primary sites for nutrient exchange between the fungus and the plant. They are ephemeral, typically lasting only a few days before being reabsorbed by the plant.

- Vesicles: These are lipid-filled storage organs formed by the fungus, either within or between root cells. They serve as energy reserves and can also act as propagules for new fungal growth.

- Intraradical hyphae: These are the fungal hyphae that grow within the root cortex, connecting the arbuscules and vesicles.

- Extraradical hyphae: These hyphae extend from the root surface into the surrounding soil, forming the vast network responsible for nutrient acquisition.

Unveiling the Unseen: Extracting and Staining AMF from Roots

To study AMF colonization, researchers must first make the fungal structures visible within the plant roots. This involves a two-step process: clearing and staining.

Root Clearing

The purpose of clearing is to remove the plant's cellular contents, pigments (like chlorophyll), and other compounds that would otherwise obscure the fungal structures. This makes the root tissue transparent, allowing the stained fungi to be easily observed.

- Procedure: Fresh or preserved root samples are thoroughly washed to remove adhering soil particles. They are then typically immersed in a potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution, commonly at concentrations ranging from 5% to 10% (w/v). The roots are often incubated in this solution at elevated temperatures, such as 90°C, for several hours, or at room temperature for a longer duration (e.g., 24 hours), depending on the root thickness and toughness. This alkaline treatment dissolves the cytoplasm and other organic matter within the plant cells, leaving the fungal chitinous cell walls largely intact (Phillips & Hayman, 1970).

- Rinsing: After the KOH treatment, the roots are thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to remove residual KOH, which could interfere with subsequent staining.

Root Staining

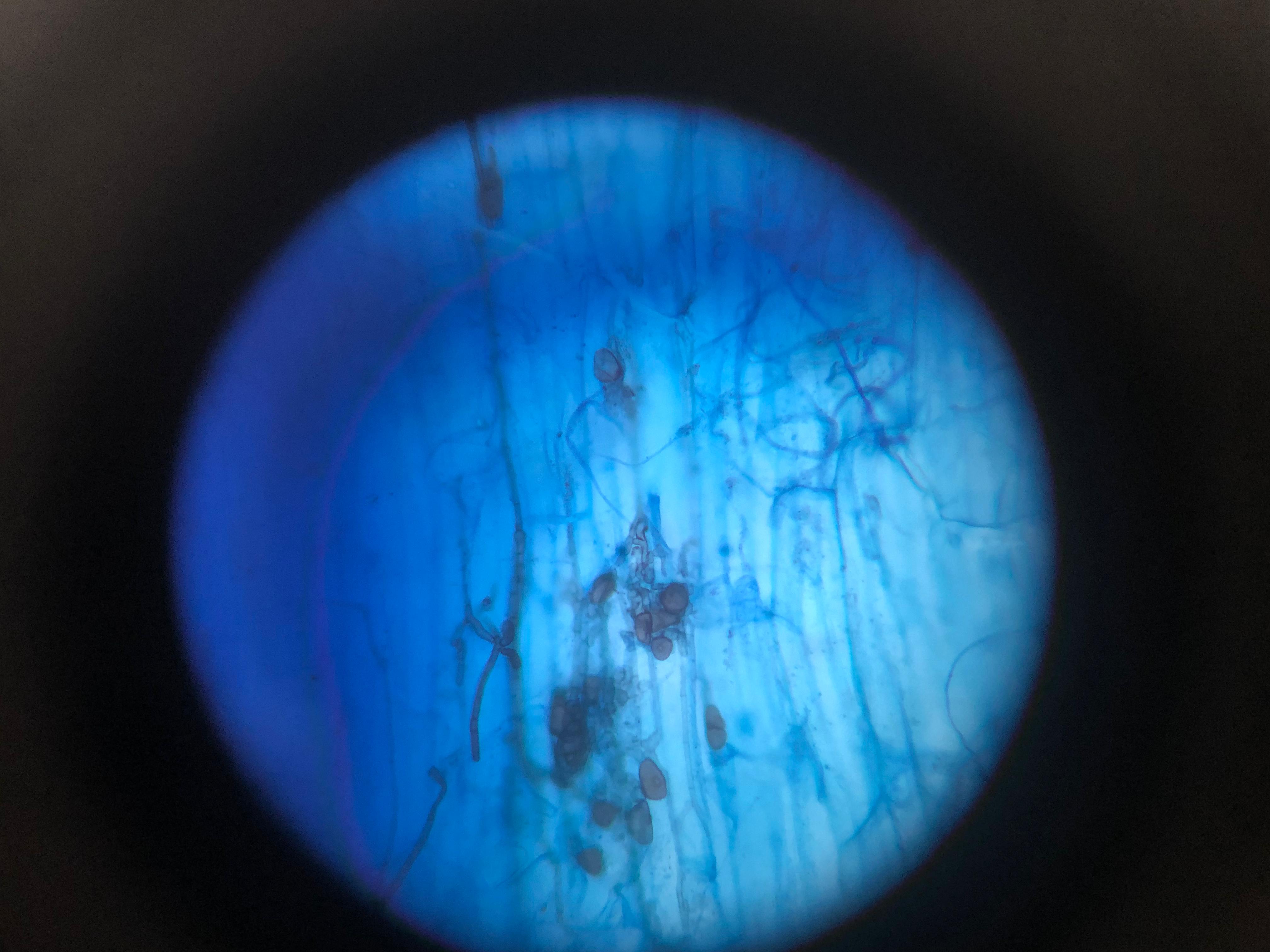

Once cleared, the fungal structures are still largely transparent. Staining makes them visible by selectively binding to components of the fungal cell walls.

- Acidification: Before staining, roots are often acidified by soaking them in a dilute acidic solution, such as 1% hydrochloric acid (HCl), for a few minutes. This step helps to neutralize any residual KOH and enhances the uptake of the stain by the fungal structures.

- Staining Solution: The most commonly used stain for AMF is Trypan Blue (0.05% to 0.1% in a lactic acid-glycerol-water solution). Other stains like Chlorazol Black E can also be used. The roots are submerged in the staining solution and incubated, often at 60-90°C for 10-30 minutes, or at room temperature overnight. The stain selectively binds to the chitin in the fungal cell walls, turning the hyphae, arbuscules, and vesicles a distinct blue or dark color (Koske & Gemma, 1989).

- Destaining: After staining, the roots are typically transferred to a destaining solution (e.g., acidified glycerol or lactic acid) to remove excess stain from the plant tissues, further enhancing the contrast between the clear plant cells and the stained fungal structures. The roots can then be stored in a preserving solution (e.g., glycerol) for later microscopic analysis.

Quantifying the Connection: The Gridline Intersect Method

Once the AMF structures within the roots are stained and clearly visible, the next crucial step is to quantify the level of root colonization. This provides a measurable indicator of the intensity of the symbiotic relationship, which can be correlated with plant health, nutrient uptake, and environmental conditions. The gridline intersect method is a widely adopted, efficient, and statistically robust technique for this quantification (Newman, 1966).

Here's a detailed breakdown of the procedure:

- Root Preparation for Observation: Stained root segments are carefully arranged on a microscope slide, often in a parallel fashion or randomly distributed, and mounted in a drop of destaining/preserving solution. A coverslip is then gently placed over the roots.

- Microscope Setup: The slide is placed under a compound microscope. The microscope must be equipped with an ocular grid (a grid etched onto an eyepiece reticle) or a digital grid overlay if using image analysis software. The magnification used is typically 100x or 200x, chosen to allow clear visualization of fungal structures while covering a sufficient field of view.

- Systematic Scanning: The observer systematically scans the entire length of the root segments on the slide. This is usually done by moving the stage in a serpentine pattern, ensuring that all parts of the root are examined.

- Counting Intersections: As the microscope field of view moves, the observer counts the number of times a gridline intersects a root segment. This count represents the total number of "observation points" along the root.

- Assessing Colonization at Intersections: For each point where a gridline intersects a root segment, the observer determines if any AMF structure (hyphae, arbuscules, or vesicles) is present within that specific root segment at the point of intersection. If any fungal structure is visible at the intersection point, that intersection is counted as "colonized."

- Data Recording: The total number of root intersections and the number of colonized intersections are recorded.

- Calculation: The percentage of root colonization is then calculated using the following formula:

$$ \text{Percentage Colonization} = \left( \frac{\text{Number of Colonized Intersections}} {\text{Total Number of Root Intersections}} \right) \times 100 $$

This method provides a reliable estimate of the proportion of the root system that AMF actively colonizes. It is particularly useful for comparing colonization levels across different plant species, soil types, environmental conditions, or experimental treatments.

The Broader Implications of AMF Research

The ability to accurately extract, stain, and quantify AMF colonization is foundational for advancing our understanding of these critical symbionts. Research utilizing these methods helps us to:

- Optimize Agricultural Practices: Develop sustainable farming methods that enhance natural AMF populations, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.

- Improve Plant Resilience: Breed and select plant varieties that form stronger associations with AMF, leading to increased tolerance to environmental stresses like drought, salinity, and disease (Auge, 2001).

- Facilitate Ecological Restoration: Utilize AMF inoculants to aid in the revegetation of degraded lands and promote biodiversity in ecosystems.

- Understand Soil Health: Gain deeper insights into the complex interactions within the soil microbiome and their impact on nutrient cycling and soil structure.

References

- Auge, R. M. (2001). Water relations, drought and VA mycorrhizal symbiosis. Mycorrhiza, 11(1), 3-42.

- Koske, R. E., & Gemma, J. (1989). A modified procedure for staining roots to detect mycorrhizas. Mycological Research, 92(4), 486-490.

- Marschner, P., & Rengel, Z. (Eds.). (2012). Marschner's Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants (3rd ed.). Academic Press.

- Newman, E. I. (1966). A method of estimating the total length of root in a sample. Journal of Applied Ecology, 3(1), 139-145.

- Phillips, J. M., & Hayman, D. S. (1970). Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 55(1), 158-161.

- Smith, S. E., & Read, D. J. (2008). Mycorrhizal Symbiosis (3rd ed.). Academic Press.